From the 12 documentary short films this year at Sundance, this is my list of the ones that really spoke to me. Unfortunately, I didn’t get to view all of the shorts this year in this category, so I am excluding Up at Night and Dear Philadelphia since I was not able to screen them. I love documentaries, and this easily could have been a round-up of all 12 documentary shorts. But, I tried to be a little more selective, so here is my stand-out picks from the Sundance 2021 Documentary Short Films Program.

A Concerto Is A Conversation — dir. Ben Proudfoot, Kris Bowers

From Jim Crow Florida to the Walt Disney Concert Hall, A Concerto Is A Conversation artfully weaves the story of two generations. Kris Bowers, an accomplished American composer and pianist is preparing for the debut of his new concerto, “For a Younger Self.” At the same time, he wants to have more conversations with his 91-year-old grandfather, Horace Bowers, Sr., who has been recently diagnosed with cancer. There’s a softness and gentleness to Conversation, as Horace talks to his grandson about his flight west from his hometown of Bascom, Florida toward Los Angeles. It is intimate, and you feel as if you’re sitting down with the family and learning these stories about grandpa.

Horace details his struggles as a Black man, even after coming to Los Angeles. At the age of 20, he was able to buy the dry cleaners he was working at and become a business owner (one that flourishes today) but he struggled with discrimination even then, forced to do much of his business by mail so that people could not tell he was a Black man. “In the South, they tell you. In Los Angeles, they show you,” Bowers, Sr. says. As his family grew, eventually Kris was born. Family photos and footage shows Horace, Sr. in the background of recitals and supporting Kris during his time in Julliard. Kris Bowers would go on to score the Oscar-winning film Green Book, as well as collaborate with artists like Jay Z and Kanye West. The short ends with grandfather and grandson at the concert hall as “For A Younger Self” plays. “[I] enjoy seeing my children and grandchildren being successful,” Horace, Sr. muses. “That’s glory in itself. It’s just something that I hope I had a little something to do with it.”

You can watch A Concerto Is A Conversation now through The New York Times.

The Field Trip — dir. Meghan O’Hara, Mike Attie, Rodrigo Ojeda-Beck

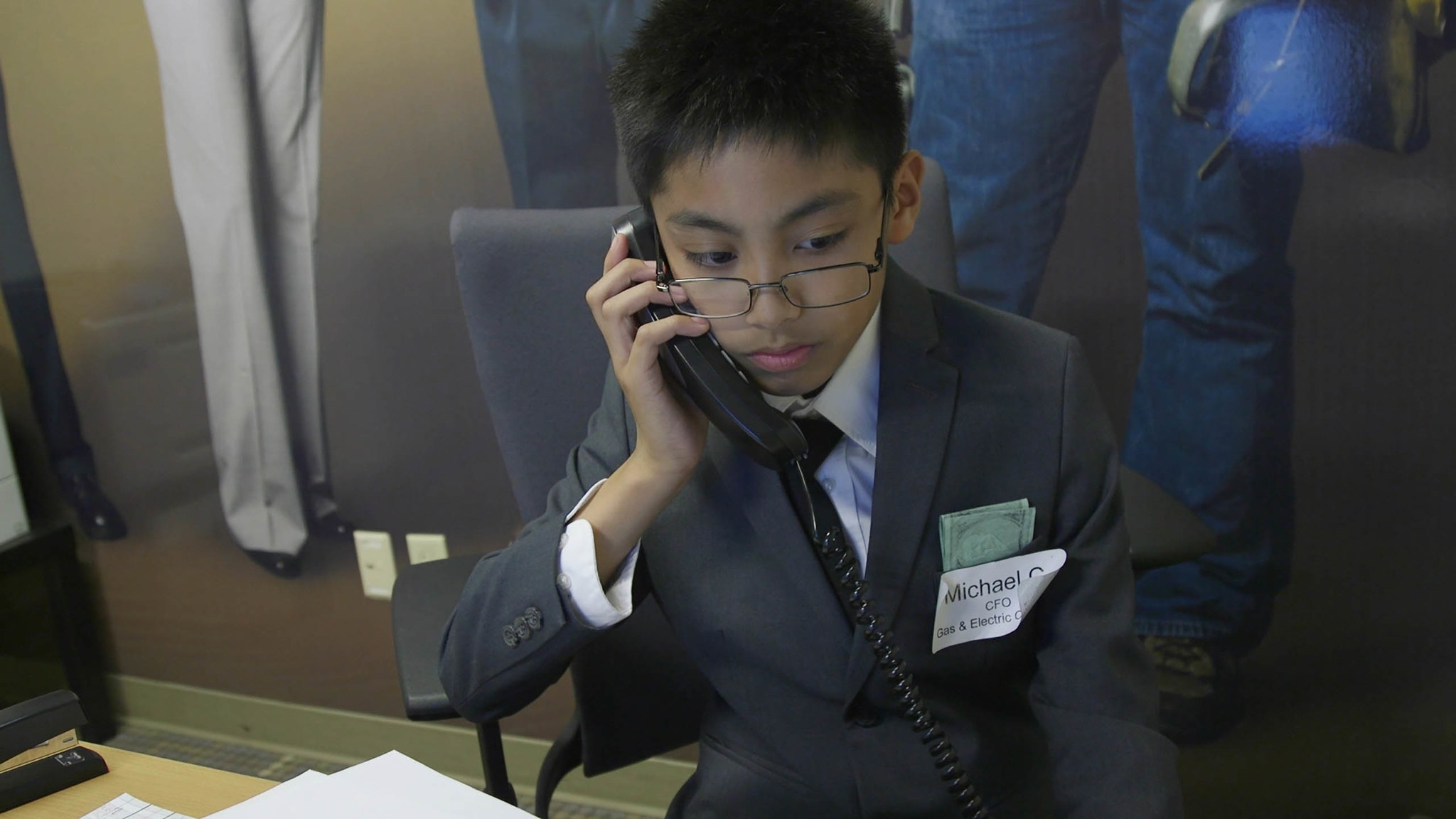

Capitalism, bureaucracy, paperwork. It all comes with adulthood in America. Entering the proverbial rat race comes with days of click-clacking away at a computer, boring meetings, and a general feeling of “Why am I doing this?” For the kids of The Field Trip, they get to experience the highs and lows of adulthood within the span of a day. Most of the 13-minute short is intercut with vignettes of kids encountering technical errors on computers and figuring out a ridiculous banking system (One kid laments, “Why does life have to be so complicated”), while also trading snacks at lunch and talking about their business. However, the deck is not stacked evenly, and CFOs among the students are chosen by teachers who believe that these particular kids are “ready for this level of responsibility.”

In this kid-friendly version of The Stanford Experiment, it is clear that a hierarchy begins to form almost immediately among the kids. In a longer scene, we watch as a CFO criticizes one of the kids working beneath him. When the kid complains that he has trouble remembering things, the CFO chastises and says, “You need to have a strong memory if you’re ever going to do good in business.” The kid replies, “I don’t have a strong memory.” The CFO replies shortly, “Everyone does. You’re just not working hard. If you work hard, you will.” It’s difficult not to see our own adult experiences in the experiences of these children. Is this what we want the future leaders of the country to become? Critical and exacting without a thought to empathy or humility? One of the adults ends the day telling the students to take what they’ve learned and start applying it to their own life. They repeat affirmations telling them they’re bright, talented, and can do anything. But can they? For some of the kids, relegated to maintenance or food service, this day wasn’t reinforcing that the sky is the limit. Will teaching our children the realities of the capitalist system help or hinder them?

You can watch The Field Trip now through the New York Times.

The Rifleman — dir. Sierra Pettengill

Few of the documentary shorts left me as infuriated as The Rifleman. Director Sierra Pettengill crafts a galvanizing timeline of the National Rifle Association, tying together gun culture, U.S. border patrol, and leader of the NRA, Harlon Carter. We learn of Carter’s rise through the ranks of the Border Patrol in the 50s, taking part in practices that have likened the patrol to the Gestapo and deported almost a million people. We also learn of his, unsurprising, detestation of gun control. Until the Black Panthers began to rise to prominence. Again, surprising no one, the NRA suddenly starts talking about gun control. About taking guns away from “criminals” and not from “legitimate hunters.” Gun propaganda is rampant at the time, with many people buying guns for the sake of “protection.”

By the 70s, Carter is a lobbyist for the NRA, once again rejecting gun control. He tells an interviewer, “Yes, I strongly feel that we’re right, and I strongly feel that we shall win.” He stages a coup within the NRA and begins his reign as the leader, getting rid of older members who might have agreed to gun control laws. At this point, Pettengill throws us back in time to the 30s, where we learn of a teenaged Carter’s coldblooded murder of a 15-year-old Ramón Casiano. Fueled by racist beliefs, he shot the boy point blank and ended up with a disgusting two years in prison. This intercut with Carter spouting the rhetoric of “guns don’t kill people, people kill people” is a sick irony. Had the young Carter not had access to his father’s shotgun, perhaps Ramón Casiano might still be alive. Carter is named as the father of the modern NRA and I’m left feeling nothing but pure rage. It is undeniable that Carter played a pivotal role in the NRA’s shift from hunting and sportsmanship to what exists today. How many people might be alive today if Carter’s life had turned out different? We’ll never know.

Snowy — dir. Kaitlyn Schwalje, Alex Wolf Lewis

I will admit that Snowy made it to this list for the pure reason that Uncle Larry reminds me of my own father, who recently adopted a tiny turtle last year. The care that Uncle Larry dedicates to Snowy? That’s pretty much synonymous with how my father treats his turtle. Daily trips to the backyard where he can crawl around and eat some grass and get some sun. Even a little hut with a blanket within his tank where he can go and sleep where it’s warm. After visiting Uncle Larry’s house for years for Thanksgiving, co-Directors Alex Wolf and Kaitlyn Schwalje decided to turn their gaze to Snowy, who seems to be trucking along after ten years of care.

They fly to London to meet with a tortoise expert, who gives advice on how Snowy can live a happier and fuller life. From their site, “Snowy’s story is a stand-in for the unexamined lives of our house pets—the goldfish, lizards, guinea pigs, and hermit crabs of our childhoods—the JV squad of house pets—the ones too small, short-lived, and expressionless to garner much of our human attention.” And while Snowy may belong to that JV squad of house pets, it’s still gratifying to see the little guy go through a lifestyle change where he can flourish as a happy little turtle and get to stretch his legs a little. This quirky little doc holds a special place in my heart if only because I see Snowy in my own family turtle.

Tears Teacher — dir. Noémie Nakai

Investigating the power and healing properties of crying, Noémie Nakai centers Tears Teacher around Hidefumi Yoshida. As a member of the frequent cryer’s club, I was instantly drawn to this docushort. I have never been shy about how easily I cry. A movie, a television show, even a commercial has the ability to leave me in shambles. However, this is not the case for many people. And as Hidefumi illustrates, many people, especially men, in Japan consider holding back tears a virtue in society. Hidefumi’s work as a “tears teacher” is contributing to the importance of mental health care in Japan. In situations where people are physically and mentally exhausted from overwork — Hidefumi’s own friend died from overwork — crying regularly can release stress.

For some, this seemingly peculiar form of therapy might seem bizarre or even humorous, but Hidefumi is right when he reiterates that crying can be an extraordinary form of stress relief and it can even boost the immune system. He states that crying regularly makes him comfortable with himself. The clips we’re treated to of his students crying feel cathartic; a release of emotions previously held at bay. As his business grows (from workshops to a crying cafe) there is a hope that as more people embrace this form of therapy, they will also begin to feel comfortable with themselves. We all need a good cry from time to time, and the tears teacher is here to help guide the way.

You can watch Tears Teacher now through The New York Times.

This Is The Way We Rise — dir. Ciara Lacy

The results of American colonialism often go unacknowledged when it comes to painting the tableau of our nation’s history. This Is The Way We Rise is a dynamic and poetic reminds of the immense loss of life that came as a result of the United States colonizing Hawai’i. Told through the voice of native Hawaiian beat poet Jamaica Heolimeleikalani Osorio, we are educated on the titanic amount of deaths that resulted between 1778, when Captain James Cook landed on the islands, to 1893, when Queen Liliuokalani was arrested, and the Kingdom was overthrown: 90% of the Native population died from disease. “That’s an apocalypse,” Osorio emphasizes. But This Is The Way We Rise isn’t just about the history of Hawai’i, it is about being Hawaiian.

After years of performing her poetry, Osorio felt burnt out. The pressure to perform and the feeling that she had nothing left worth saying wore on her. It is at this point we learn about the conflict on Mauna Kea. Since the 60s, thirteen telescopes have been built on Mauna Kea, a coveted location for telescope building. However, all of this was done without the consent of the Native Indigenous Hawaiians who have viewed the peaks of Mauna Kea as sacred to their religion. Now, with the threat of a fourteenth telescope (the Thirty Meter Telescope), Osorio decides to join those encamped along the access road to protest the building of the telescope. Through this experience, she finds inspiration once again and a new perspective to being a Hawaiian. In a stirring conclusion, Osorio performs a poem for her fellow protesters. She says, “Being there, I had voice again, I had something new to say.”

You can watch This Is The Way We Rise now through PBS.

To Know Her — dir. Natalie A. Chao

Much like Snowy, I felt a real kinship to director Natalie A. Chao’s To Know Her. As a child of Chinese immigrants, there is always a divide between yourself and your parents. A cultural divide, a language divide, a generational divide. Chao delves deep into her mother’s past through the lens of home videos that her mother loved to shoot. Lamenting, she says, “How do I love you when I don’t know you?” She struggles facing letters of her mother’s that she can’t translate, and instead watches old videos of her parents when they were young.

When her father asks her why she prefers these old videos, she replies that she sees parts of her parents in those videos from the past that don’t exist today. She sees her mother in those videos like a “normal person” and not a parent. It’s true that when people become parents, a part of their own autonomy is lost to the family, even more so for immigrant families where a parent must not only adjust to becoming responsible for the family but also adjusting to the newness of a foreign country. In the end, To Know Her is intimate. It is the story of one family, of a woman trying to learn about her mother after her death, cobbling together glimpses into the past to learn about the woman who was so beloved in her family.

When We Were Bullies — dir. Jay Rosenblatt

In a series of unexpected coincidences, director Jay Rosenblatt is taken on a journey into his own past that leads to an examination of a bullying incident 50 years ago. When We Were Bullies truly hits you with plot twist after plot twist. Rosenblatt’s entertaining directing style jumps from stone to stone in a mystery that it seems even he doesn’t know the answer to after bringing the film together. After realizing that he and all of his classmates bullied one of their fellow classmates, Dick, back in fifth grade, Rosenblatt becomes obsessed with the incident. He creates a documentary in 1994 about male socialization, The Smell of Burning Ants, and ends up being contacted by Dick who finds out about it through word of mouth. Dick tells Rosenblatt that he’s okay and been living as a TV producer for the last 20 years.

But the story doesn’t end there. Rosenblatt proceeds to interview his own classmates about the incident, and many remember it, despite the time that has passed. He even tracks down their teacher, Mrs. Bromburg, who was a strict and exacting educator. What makes this docushort interesting is how unsure of itself it is by the end. Are we against the bullying of Dick? Yes. But then Rosenblatt shifts some blame to Mrs. Bromburg, who called the students animals after breaking up the bullying incident. He also references his own younger brother, who died when he was young, in a reference that doesn’t seem to truly fit within the realm of the docushort. The short ends without hearing from Dick himself, who likely does not want to be reminded of a harrowing moment in his childhood. I feel very conflicted about When We Were Bullies. On one hand, it’s a very compelling story, but on the other, it seems to not know where it stands on the whole incident. There is an air of uncertainty that intrigues by the end of the film.

These short film reviews were based on the documentary short film programs at Sundance Film Festival 2021.