When we look back at pieces of art that changed our entire society, we’re often dismayed to see our prejudices and societal failings on full display. I’ve been thinking a lot about The Birth of a Nation lately, and not just because Spike Lee recontextualized it in his remarkable BlacKkKlansman. The Birth of a Nation is arguably the most important film in history, what with creator D.W. Griffith’s use of analytical editing, shot construction, tracking movement and more. Basically, Griffith created modern cinema. He just did it in a racist, sickening and repugnant fashion, adapting a novel called The Clansman to the screen for a rapt audience.

It’s hard to overstate the narrative reach of The Birth of a Nation. It was the first film ever to be screened in the White House, and President Woodrow Wilson – the former president of Princeton who was also the originator of the League of Nations – said the film was like “writing history with lightning.” It reinvigorated the Ku Klux Klan across the United States. And, as light must always shine in the darkness, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People challenged the film across the country, rightly and righteously increasing the young NAACP’s stature. I could go on, but my point is this: advances in art always reflect the time in which that art was created. While form and function can be split critically, they’ll always be infused in the final product.

Now, the world of comics seems to have reached a space apart from other forms of popular entertainment. Take, for instance, David F. Walker’s excellent new series The Hated. His post-Civil War story centers around a truce between the Confederate States of America and the Union States of America, and a former slave turned bounty hunter who tracks Confederate war criminals into the south. HBO’s Game of Thrones showrunners had a similar premise, but couldn’t even begin to get their series off the ground once it was announced. And while Walker’s writing pedigree is much stronger – Bitter Root, Naomi, Cyborg, Luke Cage, etc. – the cost of the average HBO season is, conservatively, tens of millions more than the cost of a graphic novel, easy. While my bet is on Walker’s story being remarkably better than the proposed HBO debacle, the general premise also had a chance of thriving in comics in a way it never could on screen.

But it’s AAA video games that have truly threaded the societal criticism needle while maintaining budgets and audience numbers more akin to their film counterparts. I mean, right now you can unlock a soldier in the insanely popular Call of Duty: Modern Warfare who features a prosthetic leg. Pretty cool. But 10 bucks will get you a gun in the online store with “dismemberment rounds” that allow you to blow off the limbs of enemy players. You don’t need to be Ambrose Bierce to feel the weirdness around the edges there.

(Think on this: sell 100,000 comics and you’re at the top of the sales chart, but get 2 million viewers – like the average episode of Mad Men – and you’re considered a failure. Meanwhile, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare made $600,000,000 in its first three days of release. Video games are… unique.)

And I continue to be awestruck, all these years later, by a character from Fallout 3 named Leroy Walker, an African American “slaver” who wants to destroy a revolutionary group located in the post-apocalyptic ruins of the Lincoln Memorial. Leroy believes might makes right, and despises the idea of an abolitionist shrine being restored. The leader of the abolitionist group, Hannibal Hamlin, is a former slave… and also an African American. As the player of consequence, you can decide to help Leroy in his quest, ensuring the destruction of the freedom movement and capturing any remaining runaway slaves, including Hannibal. Imagine seeing THAT little wrinkle on the just announced Fallout HBO series.

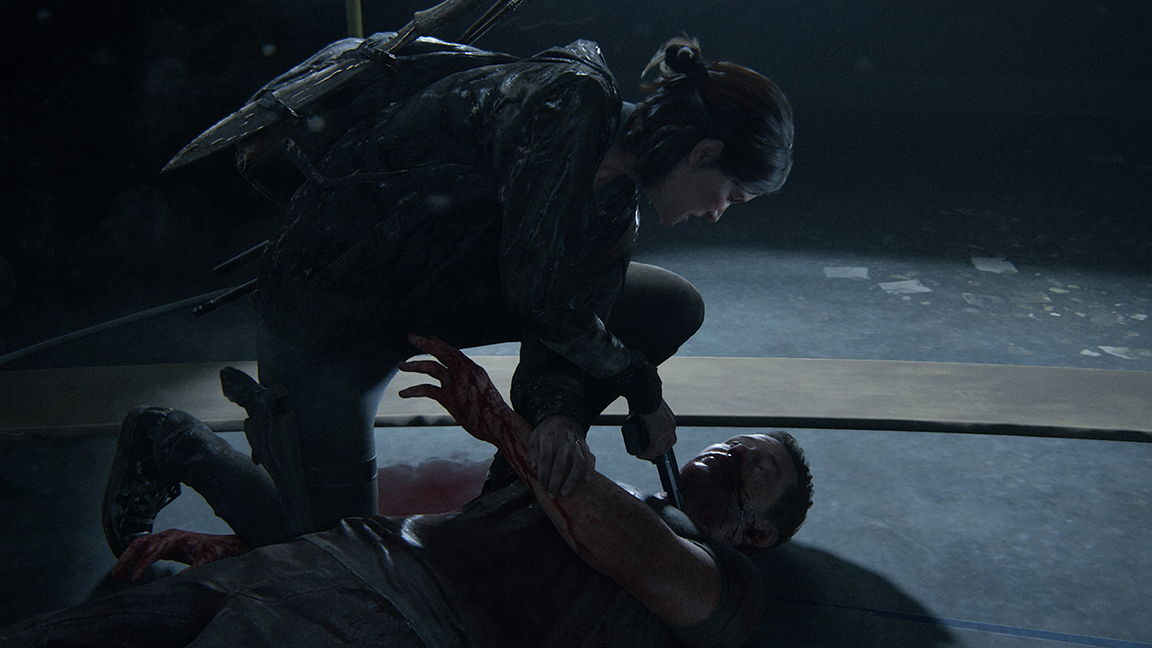

But while Fallout thrives on satire, irreverence and irony, there’s no such distance in The Last of Us Part II. Imagine, if you will, a 30-hour movie where roughly half of its run time involves your main characters murdering other characters in graphic detail. Hangings, crucifixions, torture, lynching, disembowelment… it goes ALMOST all in. And I continue to wonder if shooting, assault and emotional violence are the true legacy of AAA videogames, what that means for the concepts of entertainment and art for the industry moving forward… and what that means for future generations looking back.

The Last of Us is about a young girl, Ellie, being escorted across a post-apocalyptic countryside by a grizzled and stoic man, Joel (aka you). Ellie’s immune to the fungal plague that’s swept the world and caused humans to turn into horrific and violent mutations. Joel’s tasked with getting her to the Fireflies, a science-based group that’s struggling to find a cure. But when they get to the aforementioned Fireflies, Joel learns that they’ll have to kill and dissect Ellie to get their answers. So, as Joel, you kill them. You kill them all. When Ellie wakes, far away from the ruins you left behind, you lie to her. She’s been tested, and she’s done. In an amazing moment, the camera lingers on her face as she seems to decide if she wants to believe you. And – for now – it seems she does.

It gave me nightmares for weeks. A profound story about sacrifice, love and loss, it created an indelible relationship between its main characters and ended on a profound note of ambiguity. Ladder puzzles aside, it was a solid previous-gen gameplay experience. Sharp, vicious, brutal and acted to absolute perfection, the PS4 remaster also featured the DLC Left Behind, which was breathtaking. With a mix of exploration, terror and lovely inclusive character beats, it almost begged the question: Do we need rote combat to deliver a great video game experience? The Last of Us Part II says, unequivocally: YES.

The sequel is about revenge, basically, and took me about twice as long as the original to finish. I didn’t have any nightmares. I just felt profound confusion, then concern, then anger. I’m still grappling with it as I’m typing. In this, The Last of Us Part II is truly extraordinary. I don’t know if I’ve ever had such a visceral, even guttural response to a game. Here’s why.

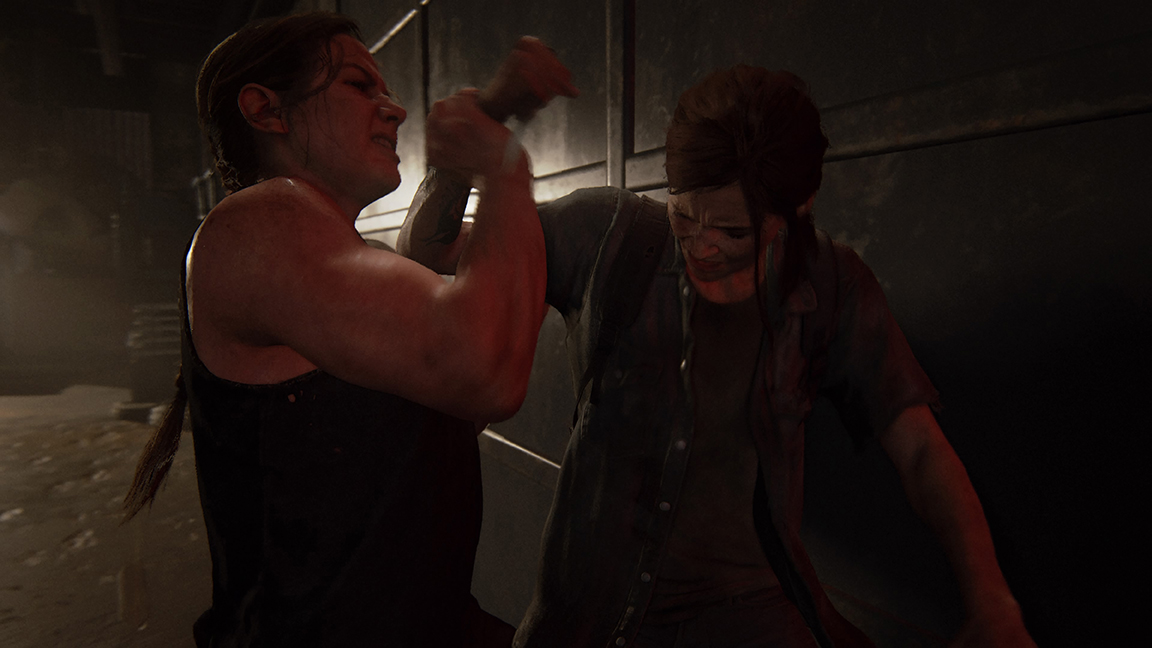

Narratively, The Last of Us Part II reads pretty simply. Joel and Ellie are now 4 years older, and have a strained familial relationship. In an awkward approximation of a Steadicam shot, Joel gets beaten to death in front of Ellie by an outside group, who leave her alive and then disappear. As Ellie, we hunt this group down, torture them for information and kill them, one by one. Suddenly, halfway through, the game shifts the player to be the leader of the group that killed Joel. This is Abby, and she’s the daughter of a Firefly scientist Joel killed in The Last of Us. In an insane story conceit, the game ping-pongs Abby BACK in time, so we meet and interact with the individuals who, as Ellie, we’ve so far successfully killed. (I found Abby’s side of the story much more streamlined, interesting and thoughtful, frankly.) The forces of nature that are Ellie and Abby then meet again and again, in brutal and spectacular fashion, until the timelines converge and as Ellie we’re forced to knife a defenseless woman until we’re not, and everyone goes their separate ways and it’s… the end.

Some of the best films of all time have shifted protagonists in the middle of their stories. The Insider, The Godfather, and most famously, Psycho, all illustrate what a powerful structure this can be in the right hands. The issue, of course, is that The Last of Us Part II is not a movie, no matter how much of its gameplay is a guided cinematic experience filled with predestined button prompt actions and extended cutscenes. The idea that the relentless revenge narrative of the first half carries no real emotional weight until the second half already hamstrings the idea of regret. We’re a Lord of the Rings trilogy away from those brutal executions before we’re supposed to consider them from another point of view. Not exactly the cross-cutting brilliance of The Limey. It might have worked on the page, but it feels dead wrong for this medium as presented, period.

But it’s the journey, not the destination, right? And what a journey! A world that’s beautifully rendered, meticulously detailed and filled with flora and fauna. Characters brought to life with some of the finest performances ever captured in a game… or, in the case of Laura Bailey’s Abby, ever. (I mean it. She transcends the platform in every way imaginable, and deserves every award she receives, and every award she doesn’t.) Sound design and music that soars and terrifies and reinforces and moves. And a story filled with diverse folks of every body type from every walk of life – Jewish, gay, transgender, Asian, devout, African-American, Caucasian and more – not to mention the fact that every playable character is female.

It’s just that every character – playable or not – is also subjected to the most horrible of events. While representation is critical, the world of The Last of Us Part II makes sure equality means violence, torture, abandonment and, in many cases, death. It surprises me that so many were angered by the diversity inherent in the game. If they’d simply played it, they could make all their cruelest dreams come true.

While Shakespeare is held up as the greatest writer in the English language, people often forget he was writing for the masses. When the Globe Theater was excavated, archaeologists found all kinds of snack remnants. Audiences were cracking nuts and throwing fruit at the all-male performers on the stage, which makes for a delightful image. Basically, you were going to entertain, or you were going to be pelted, no matter how good the words were.

Shakespeare’s tragedies tend to be connected with the term catharsis. Basically, going through a traumatic experience with the characters on stage allows the audience to learn about – and then expel – the fear inside us all. This bleeds into Julia Kristeva’s concept of the abject and the horror genre pretty seamlessly, which in turn bleed right into The Last of Us Part II.

The question is, and I think it’s an important one, what exactly are we expelling with a game like this? Writers much better than me, Tom Bissell amongst them, have wrestled with this unique video game issue on personal and professional levels for years. Here we are, at the end of a generation of videogames, with just more blood on our hands.

Why is the history of video games built on unmitigated, endless violence? And why do we demand depravity in our big budget – and I mean BIG BUDGET, AAA, CRUNCH TIME GO – game experience? The criminally underrated Death Stranding virtually begs you to forgo killing, though it still builds much of its gameplay on “rubber bullet” gunfighting. But a “walking simulator” didn’t fit the bill for a lot of players and critics. A murder simulator – and make no mistake, this is an entire industry we’re talking about here – can, does and perhaps always will.

Ludonarrative dissonance is a phrase uniquely associated with videogames. To wit: What happens when the story of the game and the play of the game find themselves at cross purposes? What does this mean for the player, their experience, video games as a potential art form and, hell, the idea of story itself? For instance, what if the cut scenes portray me as a wonderfully heroic cowboy chap, but in the game world I torch every settlement I see? In other words, who, as the player, am I? This, incidentally, is a critique lobbed at the idea of video games as art. How can it be a singular work if it can’t even follow its own internal rules?

What’s intriguing to me is that any dissonance I felt in the Last of Us Part II came straight from the creators themselves. In one highlighted exchange, Ellie chases down one of Joel’s killers and demands information about their ringleader in exchange for a quick death. Under the glare of red lights, covered in blood, Nora says she’s not giving up her friend. The game demands we repeatedly hit the square button as the camera holds on Ellie, swinging a pipe, blood splattering across her face as she relentlessly breaks Nora. Then it cuts to black.

When we come back to Ellie outside of her home base, her clenched fist is shaking. She’s tortured the information out of Nora, and it’s weighing on her in ways it’s hard to imagine. There’s a tender scene between Ellie and her girlfriend, Dina, and a tear falls down Ellie’s cheek. As Dina holds a shirtless, scarred Ellie close, we once again stay on Ellie’s face. What hath we wrought?

Except.

At this point in the game, we’ve murdered roughly, I don’t know, 100 people? We’ve bashed them, shot them, pointed our guns to their temples and then slit their throats (in one of the game’s worst and most inexplicable animations, shhhh and stealth indeed). We’ve PLAYED. In the Last of Us, baddies would bump into Ellie, not reacting to her. Now our allies simply get in our way, blocking us or moving us around. Combat is also still rooted in the last gen. I mean, we jump and go prone as we desperately toggle through our obtuse gun menu, weaving like a drunken sailor through firefights, taking shotgun blasts to the face while racking up assorted trophies for finding trading cards and fetishistically upgrading our guns at random tables. And how about that Y button? Hitting it over and over again, a bullet here, some material to make a Molotov cocktail there (which we automatically light when we bring it up in our inventory), sometimes breaking the flow of dialogue central to the experience… and on it goes.

Have we killed dogs yet at this point? Oh, gentle reader, we shoot dogs. We blow them up with explosive arrows, we set traps galore and marvel as they’re blown apart by fire and fury. If it can bleed, it’s set before us, and so we kill. We kill and we kill and we kill. It’s like the Halo corridorsof yore, only now we’re fighting outside and it’s a layer of baddies who call out each other’s names and set dogs on you, or some mutated fungus monsters who need to die post haste for that next cutscene PLEASE.

So, why does beating Nora to death mean something different to Ellie? Because it’s a cutscene. And who Ellie is in her cutscenes versus who she is in the game are two very different people, player be damned. And, it’s important to note, we’re not SHOWN the actual torture. We don’t SEE the point where Nora, pulped, gives in to Ellie’s demands. We’re spared this. Something even the creators were concerned about us actively participating in, perhaps. Correct? Cowardly? Something for The Last of Us Part III?

There’s another scene earlier on when Ellie and her girlfriend fall into the clutches of a paramilitary group. Ellie is tied up, helpless, a gun leveled at her head. Dina comes to her rescue, shooting one of Ellie’s captors but missing the second, Jordan. He subdues Dina, and as Ellie looks on, he slowly puts his gun away and casually walks toward her prone form. Then he assaults her, crouching over her body, placing one and then both hands around her neck. She struggles, but he’s on her, and there’s nowhere for her to go.

The square button once saves the day, as you cut yourself free and then help Ellie embed a knife into Jordan’s neck. But here’s the thing: for a game purportedly about the emotional ramifications of violence, there’s NONE here. You pick up some guns, kill some baddies and after a couple lines of dialogue, it’s all in the rear view, baby! As a former caseworker and documentarian, I’ve had guns pointed at me twice in my life, and while you can make the argument these characters are okay with that particular threat, I was dumbfounded to see so little attention paid to the aftermath of the assault in this very early game encounter. There’s a glibness to this that I found, frankly, disconcerting.

And thus comes my central and overwhelming dilemma associated with The Last of Us Part II. Because the game we see and the game we play are so fundamentally at odds, I still can’t get my head around it. The discrepancy between violence as the primary gameplay mechanic and violence as a cautionary tale is so profoundly at odds with itself, it’s hard to articulate. Can a game be anti-violence and still play, fundamentally, as a murder simulator? Is this the Wild Bunch of our time? It’s certainly not Saving Private Ryan, which used its graphic nature and skip-bleach cinematography to simultaneously unveil the immediacy of war while extoling the sacrifices of its soldiers, threading its own weird needle. And, I continue to wonder, who else is playing this game? No, I’m not screaming “think of the children” into the multimedia tornado. But, if a high school kid snagged this on launch day (as many in my neighborhood did), what are THEY getting out of this – what should we call it – heightened experience? What are they learning? Where does it leave them?

Which, incidentally, brings me back to the end, and where The Last of Us Part II left me.

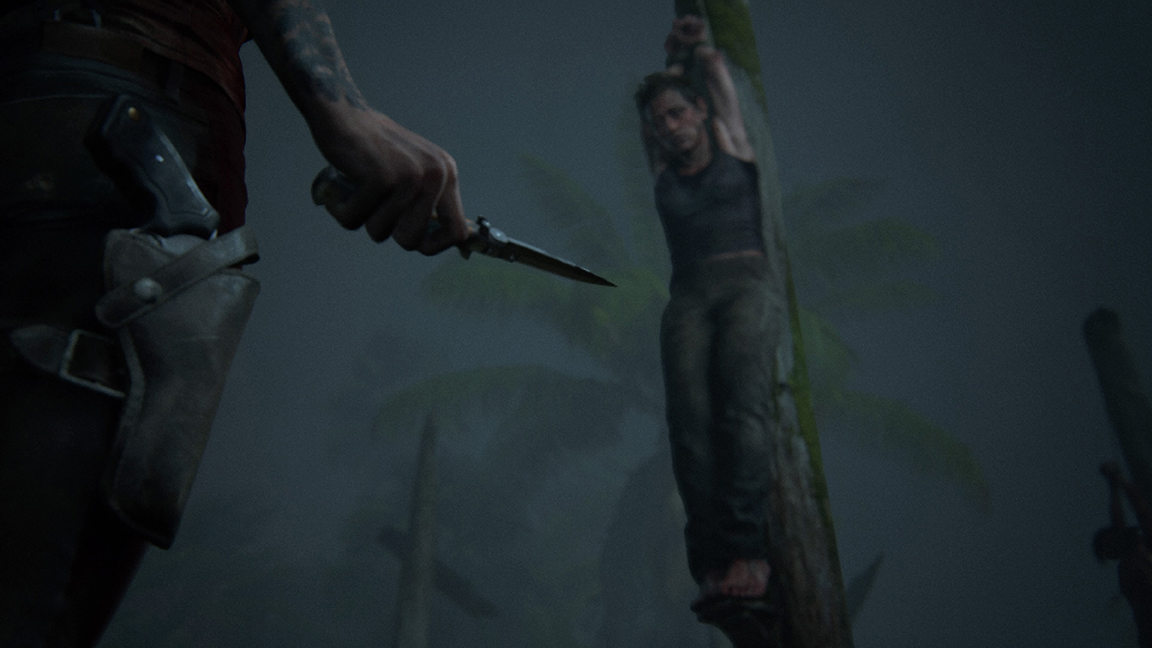

Abby killed Joel and let Ellie live. Later, Ellie killed all of Abby’s friends but Abby beats Ellie and Dina almost to death…then lets them live. The game goes on. And on. And ON. After some fait accompli dialogue, you’re back playing Ellie as you leave Dina and your baby behind, get truly hurt in a variety of ways by a variety of sharp implements, kill a whole bunch of Rattlers (slavers, a group the gamemakers have strategically created that anyone can get behind killing), track Abby to the beach (Abby’s crucified next to the young, transgender boy Lev for trying to escape) and then pull her down.

In a cutscene, Abby carries Lev to the shore and places him in a boat. She shows you a second boat, offering you an escape, a peace-offering, the cycle of violence between you finally complete. And then you place your knife to Lev’s throat and demand Abby fights you to the death, or else. Wait, what?

You don’t choose this, of course. The game demands that this happen.

At first, like Julia strapped to her chair in Nineteen Eighty-Four, I refused. I let Abby kill me, over and over again. (The Last of Us Part II revels in death animations. When you die, you die in a graphic and bloody fashion, beautifully rendered with a chilling sound cue.) I would not allow myself to participate. Was this how I was supposed to feel? Was I supposed to break myself out of the moment, disgusted with who I was, what the game had made of me, what it was asking me – making me – do? Was this the point of this entire insane reveal, to make ME question what and why I was even playing in the first place?

Eventually, though, I acquiesced. I hit the buttons and I slashed and I stabbed and I strangled and life went on for the characters, and for me, and if you’re reading this then life went on for you too, and I hope you’re healthy and happy and safe.

The Last of Us Part II is in many ways reprehensible: a bloody, misguided mess. It’s also one of the most challenging and important video games of all time.

I can’t wait to play it again.

Justin Zimmerman makes films and comics. He was not paid for this article and he bought his own digital copy The Last of Us II. He also took the stills accompanying this piece. You can see more of Justin’s work at www.brickerdown.com.

There are so many great observations made here. A particular thread stuck with me and propelled a second reading this morning.

I kept thinking about these points:

“And I continue to wonder if shooting, assault and emotional violence are the true legacy of AAA videogames, what that means for the concepts of entertainment and art for the industry moving forward… and what that means for future generations looking back.”

Add to: “Can a game be anti-violence and still play, fundamentally, as a murder simulator?”

And finally: “who else is playing this game? No, I’m not screaming ‘think of the children’ into the multimedia tornado. But, if a high school kid snagged this on launch day (as many in my neighborhood did), what are THEY getting out of this – what should we call it – heightened experience? What are they learning? Where does it leave them?”

As the author, Justin, draws excellent parallels to the medium of film and that has me thinking about the difference in a film’s audience versus a video game. I’ve found that the audience is often the weakness in a director’s intent. For example, try watching a screening of Stanley Kubrick’s ‘Full Metal Jacket’ (1987) in a theater. The powerful anti-war message Kubrick crafted is largely lost to the nostalgia of audience members quoting famous lines or imitating the Vietnamese sex worker. On the smaller screen, we have examples like Don Draper of ‘Mad Men’ or Walter White of ‘Breaking Bad’ as idolized figures by some who miss that the entire point of their series is that these are bad people doing bad things. The consequence plays out as people emulating the wrong message from these properties. (Men embracing Draper’s or White’s chauvinism and style, for example).

Video games, as Justin explores, contain a different risk with the already inherit tendency for an audience to miss the intent of the art. To misinterpret a film or book requires some reflection /after/ viewing (with an opportunity to catch the true thread). Video games empower the audience to reflect or act immediately or even during the delivery of the message. I would content then that a game can’t be anti-violence while allowing the player to act out violence without consequence. Kojima Production’s ‘Death Stranding’ (2020) is a great foil to use here. Hideo Kojima, the game’s director and auteur, came to fame helming the ‘Metal Gear’ franchise. As ‘Metal Gear’ evolved through the years, Kojima introduced more and more options to avoid lethal force (often rewarding players that embrace non-lethal tactics). Nevertheless, ‘Metal Gear’ has a fetishist level appreciation for firearms and produced a generation of fans that emulated that love for weapons of war. Kojima tries a different tactic in ‘Death Stranding.’ Non-lethal gameplay isn’t rewarded. Lethal gameplay (against humans) is penalized, made extremely dangerous, and an outright inconvenience for carrying out the objectives of the game. The main themes of ‘Death Stranding’ aren’t in themselves “anti-violence,” but by being a game about connections and valuing life, and by penalizing fatal violence, the game is ultimately anti-violence.

Compared to the circumstances described in this article, it appears that ‘The Last of Us Part II’ removes a true capacity for a player to take away an anti-violence message by featuring ultra violence as the rewarded mode of play. In my opinion, it is not enough to speak out against that which you oppose. We must act in opposition and remove the incentive. If you are anti-violence, violence cannot be permitted or, at the minimum, be rewarded.

This matters for a AAA video game precisely because of the last point made by Justin quoted above. It is my hope (though I acknowledge in some cases it won’t be) that most individuals, especially younger people, won’t have lived experiences that prepare them to contextualize or critically examine the use or nature of violence in a video game like ‘The last of Us Part II.’ There is no age limit or mile post to reach that would guarantee someone could or could not process the media they consume. However, when you have a title that is pushed and promoted as extensive as a AAA title, it is going to be consumed as entertainment first and instructive second. The violent mode of play then has the opportunity to be casual (passively) absorbed by the player. I firmly believe that violence in a video game does not cause violence in the real world, but it can desensitize or minimize our reaction to real world violence.

Each title that aims to capture a “AAA” distinction is going to look at the success of their peers and work to ref or expand on them. This is how post-modern art functions, in communication with what came before and with itself. Games have continued to grow in complexity, visual style, realism, and narrative. There are very few Western made AAA games that exist that are not centered on violence, gun play, or bloodshed. Justin is spot on in observing that the legacy of our AAA games is already “shooting, assault and emotional violence.” As studios compete for the next major success, the money is following titles or ideas that build on the demonstrated success of other titles. It may be the pragmatic decision to use violent gameplay to sell a game focused on the pitfalls of revenge and speak to an anti-violence message, but that decision undermines the intent.

(This was a phenomenal read and I keep thinking about it a week later.)

“But here’s the thing: for a game purportedly about the emotional ramifications of violence, there’s NONE here. You pick up some guns, kill some baddies and after a couple lines of dialogue, it’s all in the rear view, baby!”

I don’t think that’s the case. I mean, in the scene where Ellie is rescued from Jordan there is no time to afterwards for her to process it. They are immediately hunted and have no choice to but to fight, sneak and keep their heads. Like most of the game, the situtation is ongoing. It is relentless. Putting everything on hold after every traumatic event to deal with its emotional ramifications would be contrived. It would also undermine the broader experience of their being no respite, of the steady erosion of the characters’ mental state as events pile up behind them while dealing with tension and potential violence in the minute-to-minute.

As it happens, we do see an ongoing reaction to all of these experiences. Ellie’s dialogue becomes shorter, flatter and her trademark quips become rarer and more bitter as the game progresses. When the quips do come, they come as an expression of relief rather than celebration. Even the expression on her face changes as the game progesses. The game doesn’t stop to tell us about the effect of all these crises with Shakespearean expositional dialogue/monologue, instead it shows their toll through how the character acts and behaves.

We don’t get this in games very often as their storytelling is often heavy-handed and clunky, so it’s easy to miss even if we’re used to processing characters in novels and movies in this way.

When the characters do get to a safe place and have the space to unload those pent-up emotions, they come hard, confused and distorted. The scene after Ellie has tortured Nora is a good example of this, as is the scene after she kills Owen and Mel and finds that Mel was pregnant. In both those scenes, the preceding killings are a catalyst to the reactions that follows, but the emotion that comes isn’t just over those individual acts but are the culmination of every stressful experience to that point.

In the post-Nora scene, we’re shown this when Ellie takes her shirt off and we see all the bruises, scrapes and wounds on her battered body. They are a physical manifestation of all the trauma she has been through to that point. When she breaks down over what she did to Nora, it’s not just about that one act but also everything that she’s been through before then, that all those events had made her capable of dealing with Nora in a way that appalls herself. That act itself was as much a spontaneous expression of everything that had happened to Ellie as it was a deliberate act of torture, which we see in the rage that builds up from the mind-game she starts out playing.

I think all of this becomes even more pronounced when you play through Abby’s three days. Much has been written about how Abby’s sections shows us how similar Abby and Ellie are, but it also shows how different they are. Abby doesn’t suffer the same emotional collapse as Ellie, even though she is going through very similar experiences. She handles violent, near death episodes with much more stoicism. She never has moments of profound regret or self-disgust in the same way Ellie does, and this is simply because she’s a soldier. She’s been a soldier all of her life and has dedicated her time since her father’s death to becoming a fighting machine. Unlike Ellie, the violence in her life has been constant, it has been organised and it has happened within a framework that attached a level of moral certainty to it.

Ellie has had none of that. For Ellie, the moral certainty of her revenge is constantly challenged by what she has to do and how it changes her. There is a conflict between what she is doing and the life that Joel had tried to give for her in Jackson (despite the spectre of his lie hanging over them both), which is ultimately resolved in the final fight with Abby.

TLOU is about its characters and its world, and everything the player does is to help understand the characters better. Having to engage in the very graphic violence isn’t supposed to make the player judge themselves (we have virtually no agency in the game’s story), it is supposed to make us understand the characters and the world they inhabit better. While we might get a kick out of brutally killing people who are looking to brutally kill us, we are regularly reminded that this is our little Ellie doing it, the conflict we feel over this reflecting the conflict that Ellie herself is experiencing.

Of course, all of this doesn’t work for everybody. A lot of people just want to play games without having to think too much about it (I know I do a lot of the time), video game stories are often just a narrative justification for the gameplay, and many games want you to feel like the character you play as a means of escapism. TLOU and TLOU2 take a different approach. They are more literary than most games and use the tropes, beats and loops of games and gameplay to help tell their stories.

While it’s arguable whether they are art or not, they certainly come closer to it than most games do. After all, art is always divisive and it exists to create debates like these.