Cast: Patrick Wilson, Kirsten Dunst, Jesse Plemons, Bokeem Woodbine, Zahn McClarnon, Jean Smart, Ted Danson

Cast: Patrick Wilson, Kirsten Dunst, Jesse Plemons, Bokeem Woodbine, Zahn McClarnon, Jean Smart, Ted Danson

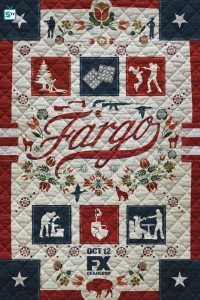

Created by: Noah Hawley (based on the Coen Brothers film of the same name)

Episodes: 10

Genres: Comedy/Drama/Thriller

Rating: ★★★★☆

Review Spoilers: Light

In all the centuries of crime fiction, there may have never been a stranger concept for a gangster drama than Fargo Season Two. It has the familiar elements of turf wars and familial complications but carries with it something different. Something stranger. It’s not the mysterious UFOs that lurk around the edges of the story. It’s not Fargo’s liberal applications of free-wheeling framing devices and visual trickery. It’s not even Fargo’s status as a fictional true crime drama (other Fargos have blazed that trail previously). No, the strange but key element that diversifies Fargo from its predecessors is that the central conflict boils down to the encroaching power of Wal-Mart.

The show’s second season* turns the plains of Minnesota and the Dakotas circa 1974 into a killing field where Wal-Mart unleashed its true power. For many years, the Gerhardt clan has dominated crime in the North, a small, family business with good values and personal service. When the head of the family has a terrible stroke, the reigns of the criminal dynasty fall to his wife, Floyd (Jean Smart).

With a theatre company of family members to oversee (each with their corresponding flaws and ways of complicating matters for Floyd), she must stand up as the Kansas City Mafia blows into town. Represented with eloquent glee by Mike Milligan (Bokeem Woodbine, in the kind of turn that stars are made of), KC wants to extend its grasp to the flush territory of Minnesota, seemingly solely to see its empire grow. Gentrification is the name of the game.

*It’s an anthology. Each season introduces a setting and cast of characters.

![[FX]](http://www.nerdophiles.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/06_KIRSTEN_SALON_048-clean-retouch-v7_hires2-470x352.jpg)

Bound by duty to respond to all of this is the local police, who aren’t quite used to this level of carnage. Luckily for them, they have a pair of real winners on their side. Lou Solverson (Patrick Wilson) is the man for any job, a cunning state trooper with a relentless ambition and sense of duty, a wife at home ailing from cancer, and a name familiar to fans of Fargo’s first season. You may also recognize his daughter as a law officer last year who may have picked up more than a few of these traits from her father. At Lou’s side is his father-in-law Hank (Ted Danson), the sheriff of Luverne, Minnesota who shares his surrogate son’s determination to see this crime drama solved.

You may also recognize his daughter as a law officer last year who may have picked up more than a few of these traits from her father. At Lou’s side is his father-in-law Hank (Ted Danson), the sheriff of Luverne, Minnesota who shares his surrogate son’s determination to see this crime drama solved.

That’s a lot of moving pieces and some of my favorites didn’t even make the list. Plus, there might be aliens. And Reagan. It is this incredible set of (perhaps too many) compelling pieces that makes the second season of Fargo the beautiful, mixed-bag experience it is.

![[FX]](http://www.nerdophiles.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/FARGO_207_0248_CL_d_hires2-470x313.jpg)

Now that they’ve written the playbook, Hawley isn’t content to simply take from it again. He has to rewrite it, throw the whole thing out and start anew. “Double the ensemble!” he said. “Add consistent use of split screen to reflect the visuals of 70s cinema! Continue to defy expectations at every turn! For better or worse!”

Last season’s finale “Morton’s Fork” seemed more interested in ensuring that the audience would never know what was coming next than anything else. What remained was a toss-up: a final episode full of surprises that exchanged emotional catharsis for surprise. In that moment, Fargo asked you to question if the ending you wanted was truly the best result, and if you only wanted it because you think you know how stories end, oh ye mighty watcher of television.

![[FX]](http://www.nerdophiles.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/FARGO_207_0128_CL_F_hires2-470x313.jpg)

It is defying expectation at the expense of pure emotion in a way that keeps Fargo constantly compelling but will always keep it a few steps removed from my coveted Personal Favorite slot. Fargo will always keep me riveted, expectations be damned, but will slide just under pieces of companion excellence like Hannibal or Rick & Morty when all is said and done. It is Fargo’s station in life, and it wears that badge so well.

![[FX]](http://www.nerdophiles.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/03_TED_LAKE_229-v7_hires2-470x352.jpg)

But unlike Walter, we are never asked to root for Lester. He is a vile, despicable excuse for a human who cares nothing for those around him. He destroys what he touches. He ruins lives. Both Fargo the film and Fargo the show know that we are not supposed to root for this guy. The second season of Fargo shatters the mold by asking us to root for the root of all evil.

![[FX]](http://www.nerdophiles.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/11_ZAHN_GARAGE_017-v7_hires2-470x352.jpg)

Gender norms keep her locked firmly in place as a wife, homemaker, and eventual mother of many in the same way that the Gerhardt’s hired gun Hanzee (Zahn McClarnon) feels overwhelmed by the trappings of being a Native American. When opportunity stumbles in front of her car, she throws herself into the life of a criminal mastermind with reckless abandon, and pulls Ed down with her for good measure.

In Season Two, Fargo made the conscious choice to bring the social issues of our time to the forefront of its story. The role trappings for both Peggy and Hanzee are overwhelming and are enough to drive one mad. They do. As the actions of the two grow bigger and bolder over the course of the season, we continue to understand them even as we lose touch with them. We can’t support their end game, but we support their reason for starting the game at all.

![[FX]](http://www.nerdophiles.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/09_PATRICK_ROAD_066-v7_hires2-470x352.jpg)

Noah Hawley makes a few decisions along the way to keep the affair from becoming “preachy” or “that show about issues” that may also leave you questioning where exactly we stand on these issues, but it is always great to see messages of social importance brought up on something as popular and well-received as Fargo. Like Jessica Jones before it, Fargo is great storytelling with enough positive social commentary to get people thinking.

Fargo is a unique television experience in a time where that phrase can also belong to a dozen other shows. It tossed of its Coen shackles long ago, although still making many distracting references to the brothers’ works along the way (there are particularly large shout-outs to Miller’s Crossing and Raising Arizona this season that took me straight out of the show; I like my dramas non-referential sosueme).

Wonderful in its approach and performance, thoughtful and sometimes confounding in its payoff, Fargo continually leaves its mark as being one of television’s premiere programs, a top-of-the-heaper among heap-toppers. Endlessly quotable. Breathlessly daring. Always Fargo.