Daredevil and Punisher represent something unique amongst Marvel’s group of superheroes, those united more by circumstances rather than authorial purpose. Both characters came into their own during the early days of 1980s grittiness but their eventual connection was forged over the years, starting in the summer of 1982 to now, when the two will share the screen in the upcoming Daredevil Season 2 on Netflix. That relationship has grown spanning decades, alternative universes and rivers of blood, and much more, one sharpened by violence, and developed into a prism to view how Marvel treats vigilantism, justice, and the intersection between ethics and crime.

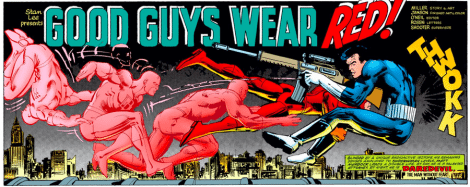

Daredevil and the Punisher first meet in Frank Miller’s Daredevil #183 in 1982 in a story where the pair brutally beat down a group of children who are addicted to PCP. It is frankly, the worst issue of Miller’s run, one that feels more like an extended “Just Say No” anti-drug ad than a piece of Miller’s epic ninja-noir series. Let’s give some context for that first encounter.

Punisher makes his first appearance in the series in Daredevil #181, one of the greatest comics of all time, more famously remembered for being the infamous issue where Bullseye kills Elektra. Frank Castle’s role in the story is pivotal albeit oft forgotten. Bullseye meets with Frank in the Ryker’s Island prison yard and, in an attempt to cut down the assassin’s ego, he mentions that Elektra has become Kingpin’s new chief assassin rather than Bullseye. Filled with rage against the ninja and, by extension, Daredevil, Bullseye plans an elaborate breakout from Rykers’ and goes after the ninja, eventually leading to her death.

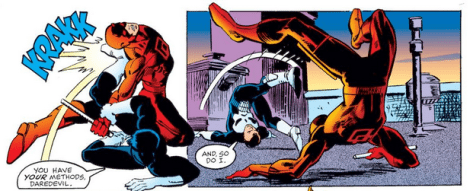

By Daredevil #183, Frank Castle has been broken out of Ryker’s by an agent representing what appears to be the CIA, who wants to use Frank as a weapon to intercept drug shipments the agency can flip to fund its operations. Frank goes rogue, accidentally murders a child in a gunfight and is off on the trail of teenage drug dealers that Matt Murdock also finds himself on. The pair battle and duel over ethics but their dialogue feels off.

Murdock repeatedly mentions that the only thing that separates him from the Punisher is that “[Punisher] kills” which is odd, considering Daredevil blatantly tries to murder Bullseye by throwing him off of a clothesline two issues before. The conflict comes to a head in Daredevil #184 when both characters target the head drug dealer, a man named, sigh, Hogman. Frank wants to kill him or arm a high-schooler to kill him. Matt, rightfully, sees this as morally wrong and tries to stop Punisher, ultimately shooting him in the gut and leaving him for dead.

As I mentioned before, this is not a good story and it feels like Miller is off his game. Matt’s dialogue is all wrong and his last confrontation with Frank is incredibly hypocritical without acknowledging that Matt’s actions are contradictory. Miller lets him off the hook but his actions here will form the backbone of the pair’s conflicts in future stories.

The pair will fight repeatedly through the ‘80s and ‘90s, most notably in Ann Nocenti and John Romita Jr.’s excellent Daredevil #257, but one of the most important stories between the pair doesn’t occur until Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon’s landmark story, 2000’s Punisher #3, part of “Welcome Back Frank,” arguably the most important Punisher story of all time. While the context of “Welcome Back Frank” would take hundreds of words to explain and require me to drink myself sick remembering the time Frank Castle turned into an angel, the important thing is that Frank is on a warpath through New York’s underworld and he wants to make sure no one will stand in the way in his bloody quest.

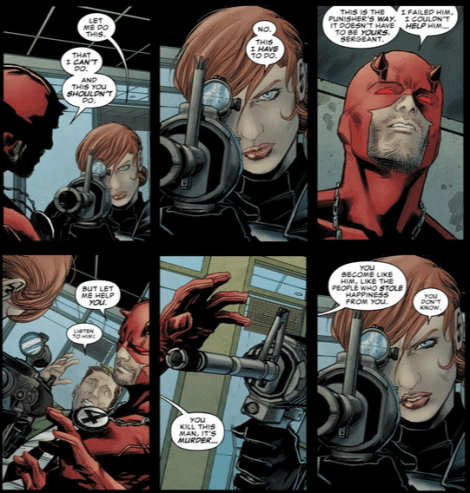

While he targets one gangster, he captures Daredevil and imprisons him with a “Saw”-esque moral conundrum. Frank is going to shoot a gangster before he’s brought to trial but he’ll give Matt a chance to stop him. All he has to do is pull the trigger of a .44 magnum and blow the Punisher’s skull off of his neck. It’s an interesting moral examination, one questioning Matt’s need to work inside the system rather than Frank’s focus on not letting social and legal structures stop his battle. It’s not a moral but an ethical struggle. Ultimately, Matt decides to kill Frank only to pull the trigger and realize that the Punisher has been a step ahead of him and has beat him in more ways than one.

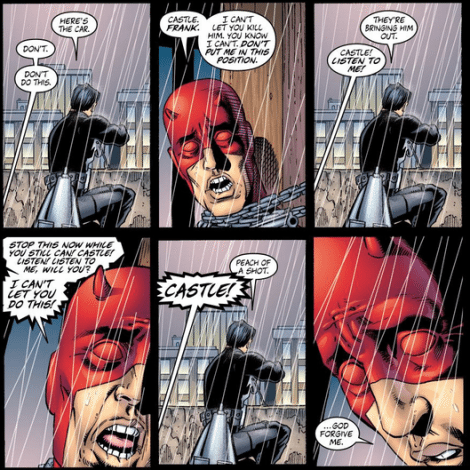

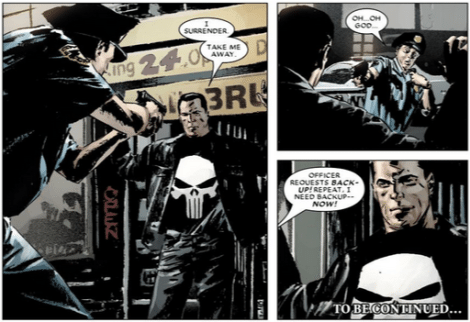

This leads up to the turning point of Punisher and Daredevil’s relationship, beginning in Daredevil The Man Without Fear #84 in 2006 (isn’t numbering a blast). In “The Devil in Cell Block D,” Matt Murdock has been imprisoned in Ryker’s with the feds assuming he is Daredevil after his identity is released in the tabloids. His time in prison quickly turns into a non-stop gauntlet against his worst enemies, including someone manipulating things from the outside. With Matt’s back up against the wall, he gives into his rage, brutally beating the Owl and Hammerhead nearly to death as the media continues to pin escalating prison violence on him. In one of the character’s most memorable moments, Frank sees the carnage Matt is facing, picks a fight with a domestic abuser, and surrenders himself to police, heading into prison to help Matt find a way out of his own personal hell.

It’s a deep, complicated look at what these two men mean to each other. Frank sees what Matt is becoming, a savage, revenge driven-animal, desperate to kill anyone he thinks in his way. At one point Frank tells Matt that this is “what it looks like when you turn into me,” trying to wake Matt from his blood-soaked fugue state. Ultimately, Punisher manipulates a riot and brings the Feds down on himself to give Matt a chance to escape and clear his name, leaving Daredevil with the words ”You don’t want to be me.” The story, written by Ed Brubaker and drawn with a sense of picturesque brutality by the great Michael Lark, is the first to paint the pair’s relationship as one that could be characterized as brotherly or inspirational. It’s Frank seeing what Daredevil means and recognizing that Matt’s symbol can be stained with blood and violence, while his own story is set.

Frank knows he can never be a hero but he’ll do what it takes to let Daredevil have that chance. It’s the kind of relationship that could make the fandom go wild if it’s spotlighted in the upcoming second season of Daredevil and remains one of the best Daredevil stories by one of comics’ most distinct voices. More than that, however, it shows something of a new take on how vigilantism and justice is seen in the Marvel Universe. Frank knows what he does isn’t and can’t be right. He needs Daredevil but he can’t fight within the same system that Matt flourishes under.

That difference, between the power of justice and the sense of closure that fatal violence brings, is often at the forefront of the pair’s interactions in more recent appearances. In a 2012 crossover with Punisher and Avenging Spider-Man, Daredevil prepares to deal with a Reed Richards created-drive, which contains information on many of the most villainous organizations on the world. Frank wants to use the drive as a weapon while Matt schemes to use the data to fight a bigger battle and ultimately Rachel Cole-Alves, Frank’s new apprentice Punisher, has to help decide between punishment and justice.

In 2013’s Daredevil End of Days alternate universe mini-series, after Matt Murdock’s death, Frank breaks out of prison to finally wipe out everyone who Daredevil couldn’t stop legally. While the series plays the violence as part of a greater mystery, the final reveal of the series shows that Frank’s actions are more altruistic, more about giving someone else a chance to be the hero he can’t. In 2015’s runaway hit, Spider-Gwen, the pair’s roles and views stay vastly the same, although their morals flip, revealing new insights into the characters’ hidden strengths while putting them in an unseen context. In this alternate universe, Frank is a barely-holding-it-together cop, hoping to save the new Spider-Woman from the brutality of the world while the villainous Matt Murdock protects the Kingpin with a series of legal loopholes and shady back-room deals, siccing his criminal enforcers only when absolutely necessary.

While the initial appearances of the characters painted them as little but violent men united briefly by a common enemy, over the course of more than three decades of comics, that relationship has changed into something darker and more complicated. Daredevil will be the hero that Punisher realizes New York City needs but one he can never be. For Matt Murdock, the Punisher will always be there, a taunting, moral black pit he must always carefully avoid. On the surface, it’s a fairly simple situation to place the two characters in, but their situation should always be one portrayed as mutual jealousy and desire. Matt always will want the freedom Punisher’s infamy and violence offers and Frank will always desire the sense of legitimacy and adoration Daredevil often receives. Pulling that off on television will be a much trickier challenge.