So, you may be looking at this title wondering what is going on. Well ladies and gentleman, for my Fall semester of my senior year, I have enrolled in a Video Games and Rhetoric class. A part of my class, I have decided to do an honors contract, which is a duty that I have to fulfill for my Honors degree. Anyways, so for my class’ honor’s project I’ve decided to write a series of… short essays on different games. These can be video games or other forms of games. Specifically, this week I am focusing and starting with a board game.

Why?

Well aside from being a super awesome game, Diplomacy has a lot of features that I think we see in video games. I mean, realistically all board games could be video games, but I think there is a certain feature of Diplomacy that makes it somehow perfect for a digital platform but also horrible for one.

In these essays, I’ll be focusing on a central topic, identity and agency in this game. Identity is something that we find in every game, and my overarching question is how does _______ influence the identity of the player? In this case, the blank is agency. A pretty basic question, but to be honest, I haven’t seen it specifically to the games that I’ve chosen to write about. So every week, I’ll be writing a little analysis of these games according to this question.

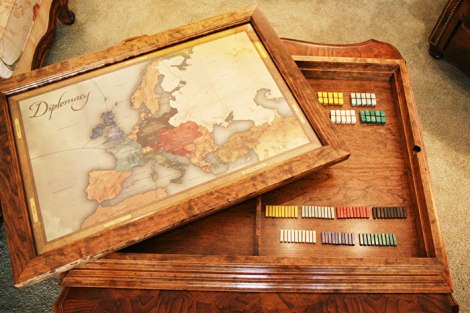

This week, we have Diplomacy. So if you aren’t familiar with Diplomacy it’s very much like Risk (but I played Diplomacy first so it’s better), basically, you enter the game in 1914 and play a country in Europe and slowly you move to take over the entire board with your country. It is a beloved game by people like Henry Kissinger, John F. Kennedy, and Walter Cronkite. I was first introduced to this game as a Sophomore in high school. My IB history teacher made the entire class play, and we split into teams and each were given a country to play as. We played this game as a class while we learned about the World Wars.

The brilliance of this game is that it is not a fast game. It’s a board game, but it’s not something that could ever really be completed in one night. Our game took weeks. It’s a game about communication, strategy, and diplomacy. You don’t have dice or cards or anything other than the board map and some pieces to move. We played it with printout maps and thumb tacks.

So what is the agency, or the goal, that the gamemaker has instilled in the players? Well, obviously it is to take over the board. But the game is made in a way that is also a great teaching tool. Instead of taking turns, like a typical board game, players submit their moves to a game master and all of the moves are made at once. Negotiations are made, and truces are broken. A game about diplomacy goes hand in hand with treachery.

In a game like this, your identity is essential to your play. Entering the game, we played as England. Every country starts off with two armies and one naval fleet, except England and Russia. England starts with one army and two fleets, Russia has two armies and two fleets. Initially our interactions involved making negotiations with France, our closest neighbor. Since we were at a disadvantage with foot soldiers, we weren’t taken as a threat and we built an alliance to help France take parts of Germany.

However, the game gets interesting when we started to make decisions like betray France and befriend Turkey, cutting up the map to split “supply centers” to win on our own. The ultimate goal to win the game is to take over half of the supply centers, and those countries that lose all of their supply centers are eliminated from the game. What do we learn from a game like this?

As a player of the game, I realized there was a delicate balance between my identity in the game and my ultimate goal. I knew as a player that I was making alliances that I would eventually have to break, but it was still important to gain the trust of my allies while there were other weaker players on the board. In my class, we played in pairs, and it was interesting to see the interactions between me and my classmates, since we knew the personalities of our classmates and determined their alliances based on our classroom friendships.

In a game that was aiming to teach us diplomacy, we learned about strategy. We won the game, but only after breaking our strongest alliance and taking them out along with a sacrifice from a third party. As players we realized the only way to win was to take out the ally that we had built such a strong relationship with. In effect, we changed who we were as players as the game progressed. What we said we would never do at the beginning of the game, eventually became our strongest play.

A game like Diplomacy was incredibly interesting to play in a classroom, especially in a small class where you can guess where initial alliances will lie. As the game progressed, you quickly learned who was strongly attached to the game, and who wasn’t. Those who weren’t as interested in the games gave their supply centers away to their friends, while some who loved the game were betrayed by their friends when found to be the weakest link.

Much of the game is focused around secrecy and making bonds with people while at the same time deceiving them. The game reveals not only what kind of person you are, but how you strategically think. The nature of the game allows itself to be played on the internet very easily, via email or even a game with a digital game master. However, it does take away a little from the face to face interaction, in my opinion.

Diplomacy can teach some pretty Machiavellian lessons in life, but it also teaches World War I in a very interactive way. I think it is a game that shows how games can be used as great learning tools, because you take on the identity of an entity in history and your own actions teach you about choices that could be made in war. Obviously it’s not a game that mimics war exactly, there are factors missing. And it isn’t like the other games that I will be talking about, I’m not playing as a character. But playing the game, I adopted the identity of a Brit, I felt pride in being “British”. I found myself looking into World War I and seeing what alliances were formed and how they might benefit me.

So if you have a group of history junkies, set aside some time to play this game. You’ll learn a lot, but you might end up ending some friendships.