We tend to see history progressing one way and comics are no exception. We see crystallizing, genre defining moments like the death of Gwen Stacy or Watchmen or “The Flash of Two Worlds” as moments where everything changes but that’s not really the case. Comics are always, in one form or another, drawing from the medium’s own history, repackaging things and fundamentally adapting to larger movements within the industry. Three new books out this week all approach this idea in their own way, each using the new standards of violence and content the comics readers willingly accept while embracing a very distinct era of the medium’s past.

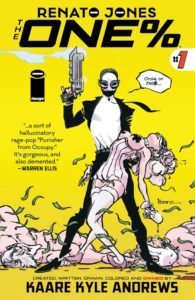

The first is Renato Jones: The One Percent #1 from Kaare Andrews. For Marvel readers, Andrews is probably best known as the writer and artist for the critically reviled “Spider-Man: Reign” miniseries, in which an elderly Peter Parker, left alone in New York after accidentally giving Mary Jane cancer due to prolonged contact with his, ahem, radioactive semen, is forced to battle a city out of control. However, his best works tend to operate outside of rigidly established characters or continuity.

Renato Jones fits that mold and it’s awfully easy to spot the books it’s referencing. It’s a series that apes the dick-swinging machismo and cocksure violence of Mark Millar’s Wanted and Nemesis and blends that style with a somewhat preachy, slightly less than timely message about the immorality of the economic elite. In a lot of ways, it’s a book that would feel right at home in 2008, with its morally twisted character, big full-page layouts and Jim Steranko-esque retro paneling.

Renato Jones stars the titular character, an orphan turned avenging assassin, out to punish those who economically exploit the rest of the world for profit and pleasure. There’s a certain macabre thrill to the Schwarzenegger-esque one-liners and fist sized bullet holes but “Renato Jones” feels like it’s trying to have its cake and eat it too. It’s an unapologetically campy yarn full of scheming trust-fund millionaires and homicidal family members straight out of the most bourbon soaked southern gothic story you can imagine but its attempts to make a larger point about economic, social, and sexual exploitation falls a little flat.

![[Image Comics]](http://www.nerdophiles.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/27578cadfc110bf3bcf1072d5f3e38bf._SX640_QL80_TTD_-e1462687117568-470x226.jpg)

Still, it’s hard to even critique the book. Andrews proudly trumpets his status as a creator throughout the comic and practically taunts his critics at every turn. In that way, it ends up feeling a bit self-aware in an achingly uncomfortable way, practically daring its audience to find fault but taunting their impotence and daring them to read further. Like Millar’s most confrontational work, it’s a piece designed to prompt only extreme reactions. Renato Jones wants to be loved, hated or both, violently and in equal measure, and I am sure there will be audience who will do just that.

![[Marvel Comics]](http://www.nerdophiles.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/358792._SX640_QL80_TTD_-195x300.jpg)

The new Punisher #1 takes a decidedly less confrontational approach and feels grounded in a version of Frank Castle readers should be very familiar with. Steve Dillon is the big draw here, the artist who practically resurrected Punisher from the dead with Garth Ennis for the landmark “Welcome Back Frank” storyline, which set the standard for how Punisher stories would be told for the next decade. Dillon’s drawing from scripts written by Becky Cloonan, Cloonan was, until recently, known primarily for her art and this is arguably her biggest assignment yet. She’s also the second woman ever to write Frank for Marvel and she’s taken a path that’s both instantly familiar and intriguing more for what it doesn’t do than what it does.

The set-up here is mostly familiar. A group of shady guys are moving illegal drugs through New York City when they come to the attention of both the DEA and the Punisher. Frank, naturally strikes first and wipes them out in a blaze of bullets and blood only to be stopped by a man from his past. It’s another story drawing on Frank’s connection to military life but that’s a route that’s often lead to some of the best stories with the character but more intriguing is what’s going on behind the scenes.

A lot of that comes down to the art itself. Fans of Dillon’s work on Marvel Knights: Punisher will instantly notice a dramatic change of coloring here. In his work across two series with Ennis, from 2000-2004, Dillon’s work tended to get a flat, slightly static coloring. Colors were muted, faces had something of a soft sheen, often used to highlight the disconnect from the allegedly super heroic world Frank Castle occupied and the bloody, realistic, consequence filled violence he commits.

In this issue, he’s colored by Frank Martin, who uses light, shadow, and shading to a decidedly different effect. It’s all shadow and atmosphere here, whether it’s Frank illuminated by a low desk lamp as he cleans a handgun or the muzzle flash of every shot casting shadows through a smashed drug den. It’s a difference that makes Dillon’s work here decidedly more realistic and also vaguely horrifying. Not to say that the coloring done by Chris Sotomayor is bad or even wrong for the book but it’s serving a much different purpose in the previous series. It’s the difference between, say, the brightly lit outdoor killing fields of “Commando” and the shadowy, up-close-and-personal hunting grounds of “John Wick.”

![[Marvel Comics]](http://www.nerdophiles.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/The-Punisher-1-Preview-3-766ff-198x300.jpg)

The writing helps push this horrific, stylistic series forward too. The fight scene that forms the backbone of the issue is notably quiet, limited to grunts, sound effects, and the occasional screamed threat or bellow of pain. Most notably, eagle-eyed readers will notice that Castle doesn’t have a line of dialogue here. He has no narration, no lines, no smarmy witticism to share with the reader or his war journal. Cloonan’s decision to have Frank operate in silence feels like the most deliberate response to Ennis’ run, which was filled with asides from Punisher as he emptied magazine after magazine into a seemingly never ending hoard of villains.

By comparison, Cloonan’s Punisher feels like a force, an animal, someone killing because that’s what he does. There’s no smug sense of self-satisfaction, only a machine going through the motions with each bullet, each punch, each cinder block to the head. Just like Dillon and Ennis did 16 years ago when they remade Frank as a self-aware killing machine performing for an audience of one, Cloonan and Dillon have remade him as a man silently doing what he thinks is right and answering to no one, not even himself.

![[Marvel Comics]](http://www.nerdophiles.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/358797._SX640_QL80_TTD_-195x300.jpg)

Thunderbolts #1 is reaching furthest back in time, seizing on the original incarnation of the team and twisting it to fit two eras. The series marks the first Marvel superhero writing job for Jim Zub, who’s made legions of fans with his independent work like Skullkickers and Wayward as well as his excellent work on licensed comics like Street Fighter, Samurai Jack, Red Sonja, and Pathfinder.

The artist of the book is Jon Malin, who has a much smaller portfolio albeit one that’s instantly recognizable. Malin’s work is fairly reminiscent of Rob Liefeld or Erik Larsen in the ‘90s. For some readers, it’s going to be a tough hurdle to clear but Zub and Malin both seem to be well aware of their individual strengths, crafting a story that feels straight out of the ‘90s in a way that’s as comforting as a well-worn VHS action movie.

Springing out of the recently wrapped “Pleasant Hill” crossover, Thunderbolts #1 sees Bucky Barnes, the Winter Soldier, leading a team of rescued villains to protect the planet, using intel from the seemingly deceased Nick Fury’s personal stashes. It feels like the best of the old and new, blending the razor thin tension of the original Kurt Busiek run on Thunderbolts with a modern sensibility, seeing the willingly amoral Bucky leading a team of villains to accomplish the missions no one else has the guts to undertake. There’s a certain grind house charm to the whole ordeal, with ripped, frequently shirtless heroes shooting their way through bad guys and frequently sparring with each other.

It’s a book that’s going to work best for readers with a certain love of ‘90s cheese, from unapologetically over-the-top action movies to the bombastic, blockbuster comics that defined the first half of the decade. The first issue is light on plot but big on characterization and shocks, setting a tone that emphasizes that anything can and will happen when this many wild, unhinged characters are in a room together. For readers who are ready for a stylistic, frequently shocking period piece, it promises to be a thrill-ride.